This translation was generated using artificial intelligence. We strive for accuracy and quality, but automated translations may contain errors. You can read the original text here.

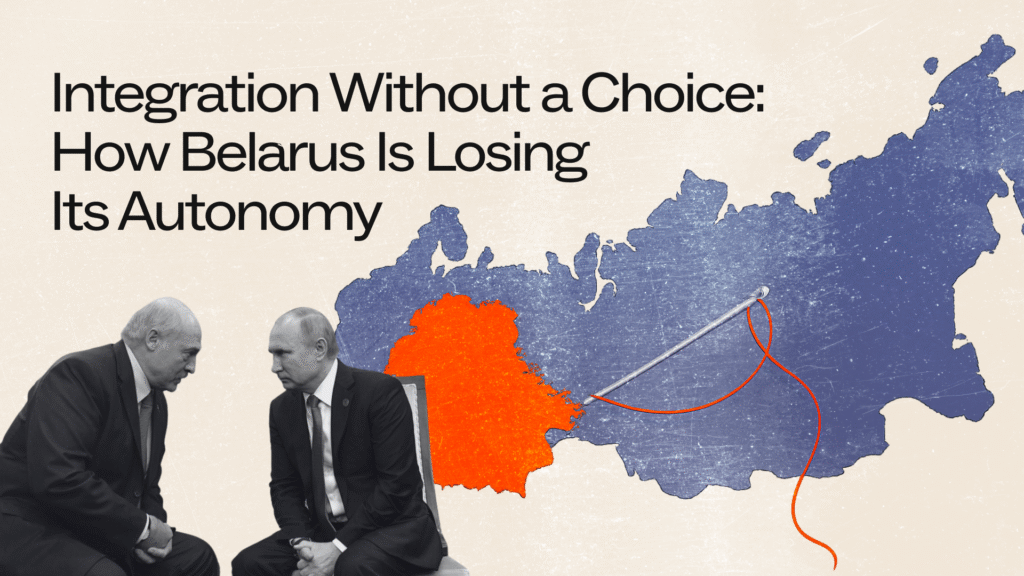

A multi-layered network of Russian influence is gradually reshaping the Lukashenka regime, embedding ideological and institutional elements aligned with the Kremlin. The convergence of Russian interests with the most reactionary segments of the Belarusian system is accelerating this process and reinforcing an already robust framework of dependency that keeps Belarus firmly within Moscow’s orbit. By Yan Auseyushkin.

To begin with, it’s important to define the actors involved. Broadly speaking, Russian influence structures in Belarus operate on several levels — each with its own degree of integration with the Lukashenka regime, its own objectives, and its own modes of impact on the state apparatus and society at large.

The first level –– the highest. The Kremlin conducts its policy through institutional engagement with state bodies, as well as through Russian foundations and media that coordinate and finance efforts to keep Belarus in its orbit of influence. The second, mid-level is responsible for the implementation of specific projects in Belarus. Here, Russian actors monitor and steer developments in the target country, often working in tandem with pro-Russian counterparts of Belarusian origin — individuals and groups embedded within local structures. The third level consists of grassroots initiatives that operate parallel to more “official” pro-Russian organizations, sometimes clashing with them over resources and influence.

Much has already been written about this first, institutionalized level. In this article, I will focus on concrete examples of public influence campaigns that fall under the umbrella of what is often referred to as “soft power.”

What the second and third levels of Russian influence look like

At the more formalized level, one finds organizations represented in the Coordinating Council of Organizations of Russian Compatriots — a network of such councils operating globally under a unified structure.

A vivid example of Kremlin-backed “soft power” is the activity of Siarhei Lushch, a politician who evolved from a once-marginal right-wing activist. In 2020–2021, he was actively involved in efforts to establish a political party called Soyuz (Union), based on a civic initiative of the same name. The initiative was launched with participation from both Russian and Belarusian political actors advocating for deeper integration between Belarus and Russia.

At the time, there were rumors — circulated by the Belarusian authorities themselves — about a potential reform of the party system and a liberalization of political life. The Kremlin sought to capitalize on this opening. However, the reform never materialized. Soyuz was denied official registration as a party and continues to exist in the form of an organizing committee — a structure once typical of opposition movements.The movement itself is not seen as toxic by the authorities. Lusch regularly organizes trips to Russian-occupied territories, often in cooperation with pro-government propagandists. Members of Soyuz collect and deliver volunteer aid to the frontlines. The initiative also holds public events inside Belarus, and Lusch appears at official gatherings alongside local government officials.

When it comes to more marginal pro-Russian activists with a critical bent, the state has resorted to light-touch repression — such as administrative charges brought against Artsiom Ahafonau and Elvira Mirsalimava. The regime’s vertical also responded harshly to individuals whose “freelance” activism began creating political headaches. This includes whistleblower Voĺha Bondarava and a group of activists behind the Telegram channel Bely Krolik (White Rabbit).

In this way, the system employs a containment strategy: assigning these actors a narrow niche, confining them to symbolic spaces of public activity while preventing them from crossing into the political arena. This model has long been established and has changed little in recent years — except for the fact that resistance from Belarusian civil society has waned significantly, due to unprecedented levels of repression.

The regime, authoritarian at its core, is hypersensitive to any form of initiative it cannot fully control — even if that initiative is ideologically aligned and outwardly loyal.

The Convergence of Russian Interests with Belarusian Reactionaries

A more telling — and dangerous — example of Russian influence is the growing alignment between the Kremlin’s interests and the most reactionary elements of the Belarusian regime. The mass purges have given rise to a new class of reactionaries: security officials, bureaucrats, and propagandists who have built their careers on repressing political opponents. In opposing democratic transformation and stifling the growth of national consciousness, they have, in effect, become “more Russian than the Russians themselves,” carrying out tasks akin to those of an occupying Russian force. Unsurprisingly, it is this group that most often takes part in Kremlin-backed influence projects.

Ideologically, these reactionaries are most closely aligned with the Russian chauvinist camp, which has coalesced around support for the war in Ukraine — and earlier, around the Novorossiya, LPR, and DPR initiatives. After the Belarusian regime abandoned its policy of neutrality, it was these actors who began actively promoting the corresponding narratives and content: stories about volunteers, trips to occupied territories, and overt support for the invading forces.

In many cases, it becomes difficult to distinguish between Russian and non-Russian agents of influence. A case in point is Kseniya Lebedzeva, who simultaneously films reports about the “Española” brigade and conducts media workshops for students at the Belarusian State University’s journalism faculty.

In the media space, the similarities and differences between the two propaganda ecosystems have been well documented. Belarusian state media operate largely according to Russian templates — adapting Kremlin narratives to the local context or launching localized versions of familiar stories. The divergence reflects the difference in strategic priorities: while the Kremlin wages a global confrontation with the West, official Minsk is primarily focused on regime survival.

A similar picture emerges with the rise of Belarusian security institutions, now increasingly forming a separate vertical structure, starting from grassroots patriotic education clubs. The deepest level of penetration occurs within the Internal Troops, commanded by Mikalai Karpiankou. Belarusian law enforcement officers are being trained by Wagner Group instructors, and joint exercises are held with Russian contract soldiers who have combat experience in Ukraine. At the Skif Special Training Center, which grooms future elites of the security apparatus, a symbolic gift — a “Wagner sledgehammer” — has been accepted as a souvenir. A disturbing, if telling, gesture.

Another relatively new dimension of this convergence is the ideologization of existing integration structures. One example: the once-stagnant Union State project received fresh momentum with the appointment of Sergei Glazyev as chairman of its Standing Committee. One indicator of this shift is the changing profile of participants at Union State-sponsored events.

For instance, in July 2025, a conference titled “The Time of the Union State: Cultural and Information Space” brought together various Ukrainian collaborators from Russia’s so-called “new territories,” along with infamous Russian figures like Sheynin and Gurulyov. Former Ukrainian Prime Minister Mykola Azarov attended virtually. On the Belarusian side, participants included ideologists and propagandists such as Volha Chamadanava, head of the Belaja Ruś association, and Andrei Kryvashyeu, chairman of the Belarusian Union of Journalists — as well as representatives of the Belarusian Prosecutor General’s Office.

In this way, Russian actors are normalizing their presence within the state information space and joint ideological platforms, working to expand their discourse beyond the niche previously allocated by the regime. What emerges is a dense and multilayered framework of influence — from Minsk’s deepening strategic dependence on Moscow (especially in the last five years) to personal horizontal networks between Belarusian and Russian operatives. Taken together, these trends point to a long-term consolidation of Belarus within Russia’s sphere of influence.