This translation was generated using artificial intelligence. We strive for accuracy and quality, but automated translations may contain errors. You can read the original text here.

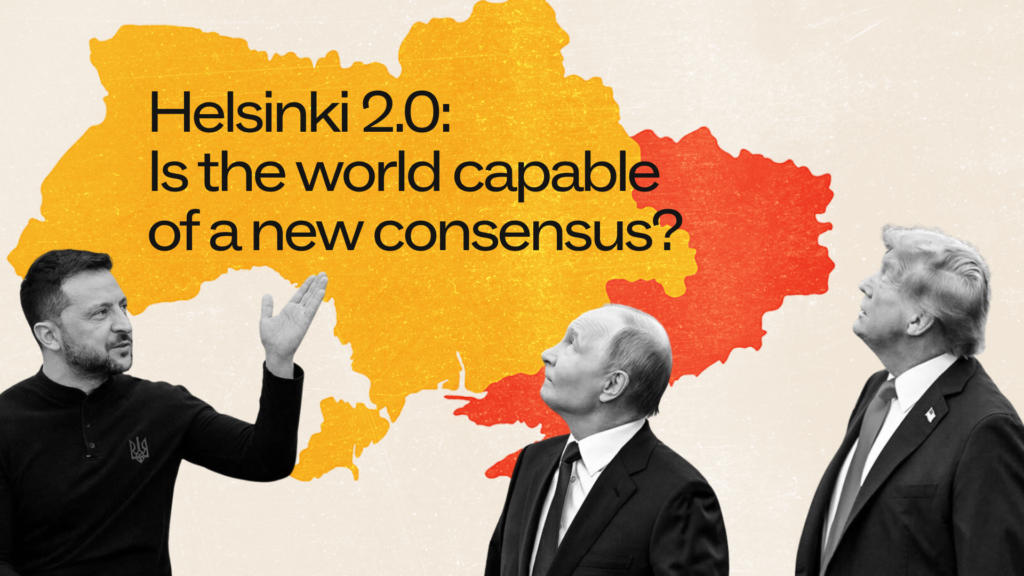

The latest rounds of peace talks aimed at resolving the Russia–Ukraine conflict have been received with cautious optimism. However, a local settlement is unlikely to yield lasting peace, since the root causes of the conflict lie in a broader regional confrontation. A broad, multilateral dialogue capable of establishing new security rules in Europe could offer a more reliable framework for resolving the conflict.

The in-person meeting between Trump and Putin in Alaska—followed by the U.S. president’s subsequent talks with Volodymyr Zelensky and European leaders—did not produce any breakthroughs, but it did outline certain trajectories for the future. Negotiating positions are increasingly shaped by a so-called “Kissinger formula”, which implies “peace in exchange for territory” alongside security guarantees for Ukraine and the reintegration of Russia into the international security structure.

To some extent, both sides are increasingly recognizing this formula as a possible basis for negotiations, although major differences remain. Russia still demands the “elimination of the root causes of the conflict,” full control over the Donbas region, and Ukraine’s renunciation of NATO membership. However, it appears willing to abandon the maximalist demands laid out in the 2022 Istanbul Agreements and the June 2025 Memorandum.

Ukraine’s position, under pressure from the United States and the worsening situation on the battlefield, is also shifting toward accepting unfavorable peace terms to avoid even worse consequences from a prolonged war.

Territorial concessions, previously considered completely unacceptable, are now at least being treated as subjects open for discussion. These changes offer hope for a peaceful resolution.

But while territorial issues may now be on the table, the question of real security guarantees for Ukraine remains unresolved. Ukraine’s chances of joining NATO continue to decline, yet no alternative system of military protection currently exists. The broader framework of European security—represented by the OSCE—is in deep crisis, and the European Union’s new security system is only beginning to take shape.

In this context, Russia’s proposals for a comprehensive peace settlement may provide a path out of the current deadlock.

A New European Security Configuration as an Opportunity

If credible security guarantees cannot be found within the current configuration of Ukraine–Russia–EU–USA, then broadening the scope of dialogue to address the foundations of a new regional security framework could open the door to alternative solutions. The subject of negotiations could be expanded to include the restoration of a regional security architecture in Eastern and Central Europe—where real security guarantees for Ukraine would become a central element. What is needed is a modern analogue of the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe (the Helsinki Process) of 1972–1975.

The Helsinki Process of the 1970s was launched following a bilateral meeting between Soviet General Secretary Leonid Brezhnev and U.S. President Richard Nixon during negotiations held in Moscow in May 1972. The documents signed during that summit laid the foundation for détente, established new security principles, and legitimized the start of the CSCE process. As a result, the basic framework of a new European security architecture was established, and tensions were reduced during the Cold War. The CSCE process was broad in scope, and its Final Act was signed by the heads of state and government of every European country at the time—including, for instance, Francoist Spain.

For Ukraine, such a process would present an opportunity to obtain more reliable security guarantees. At the same time, it could also meet Russia’s long-standing aspirations to participate in shaping a new global security system—ambitions repeatedly voiced by President Putin and his representatives. For example, in his address to the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs last year, Putin stated:

“Clearly, we are witnessing the collapse of the Euro-Atlantic security system. Today, it simply does not exist. It must be essentially rebuilt. This calls for joint efforts with partners and all interested countries—and there are many—to develop our own approaches to Eurasian security and then present them for broad international discussion.”

Today, of course, Putin will attempt to extract the maximum possible from Trump. His ideal outcome resembles a “new Yalta” — that is, a division of global spheres of influence between Russia and the United States, or perhaps Russia, the U.S., and China. However, these ambitions run up against geopolitical reality: Russia can no longer credibly claim the status of a global power and remains, at best, a regional force.

Once Putin accepts that a “new Yalta” is out of reach, he will face a dilemma: to continue confrontation or to attempt to build a new system of collective security in Europe. The experience of diplomacy in the second half of the 20th century suggests that even for so-called “empires of evil,” confrontation is not the only option.

The Regional Dimension of the Conflict

The ongoing Russia–Ukraine conflict remains unresolved largely because its root causes lie in a broader regional geopolitical confrontation. Russia’s initial aggression in 2014 stemmed from its attempt to prevent Ukraine from signing an Association Agreement with the European Union — a move that triggered the Revolution of Dignity, a change of government in Ukraine, and Russia’s subsequent invasion.

All countries of Eastern and Central Europe, as well as the EU’s eastern neighbors, continue to experience the direct or indirect consequences of this geopolitical conflict, with war being its most extreme manifestation. The struggle between pro-Russian and pro-European forces in Georgia, Russian interference in Moldova’s elections, the Belarusian regime’s orchestration of a migrant crisis on the borders of Poland and the Baltic states — along with its complicity in the aggression against Ukraine — and efforts to destabilize Eastern Europe and the Balkans are all episodes of a single, ongoing crisis. This is a crisis of a regional security system unable to restrain Russia’s aggressive ambitions.

A temporary truce in the war may be achievable, but without efforts to establish a new framework for collective European security — or at least a regional East European equivalent — a sustainable peace will remain out of reach.

It is vital that any such process be inclusive and open to all parties affected by the security crisis. This could involve regional powers such as Turkey, as well as blocs of neutral or observer states. Within such a framework, countries like Belarus or increasingly authoritarian Georgia could also have a meaningful role. For them, internal democratic shortcomings should not become a barrier to receiving external guarantees of sovereignty and protection from neighboring powers’ aggressive intentions.

What Does All This Mean for Belarus?

Belarus is often dismissed due to its dependence on Russia — a view that is only partially accurate. In the context of war and stark divisions between opposing sides, Belarus’s position increasingly resembles that of a Russian satellite. However, in periods of reduced tension, a grey zone opens up for Aliaksandr Lukashenka’s regime — which he uses to pursue alternative sources of support beyond Russia. The extent of Lukashenka’s room for maneuver depends on the breadth of the Russia–West dialogue window: he cannot go further than Putin in his relations with the U.S. or the EU. Lukashenka likely senses these limits better than most and knows how to exploit even the narrowest of opportunities. If Russia begins moving toward improved diplomatic ties with the U.S., Belarus will follow. This process is already underway through contacts with members of the Trump administration — and even a personal phone call between the U.S. President and Lukashenka, who until recently remained in diplomatic isolation.

It would be naive to interpret Trump’s call to Lukashenka as an attempt by the U.S. to pry Belarus away from Russia’s orbit. Neither side has the tools to do that, and both know it. Still, for Lukashenka — and for Belarus more broadly — this represents an increase in international agency. More such opportunities are likely to arise during the peace process, in which Belarus will seek to participate in any capacity possible. Expanding this process to a regional scale would ensure Belarus’s formal inclusion, despite the ongoing sanctions regime.

This evolving situation will also raise the question of the political agency of the Belarusian opposition — especially its key figures and structures: Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya, her Office and Cabinet, and the Coordination Council — all of whom enjoy a degree of international recognition. Given their current state and limited capacity, they are more likely to be spectators. However, predictions of their political demise are equally unrealistic. The Trump administration, for instance, is unlikely to discard tools that undermine the legitimacy of its counterpart, Lukashenka. EU leaders are even less inclined to do so. This suggests that the democratic Belarusian opposition could play a peripheral role in the regional settlement process — although their chances remain slim.

The Belarusian regime’s desire to improve its image and be included in the peace process may lead to the release of political prisoners and a loosening of political repression. At the same time, hopes that such a process will culminate in a national dialogue between the regime and democratic forces, followed by real democratization, remain utopian.

Potential Initiators

The conflicting parties themselves are unlikely to initiate a new Helsinki Process. Although Russia has declared a willingness to discuss a comprehensive peace settlement, it is incapable of leading such a process due to its current status as the aggressor. Ukraine would have more potential to do so, if not for its narrowly configured geopolitical lens, which struggles to fully grasp the regional context.

The OSCE itself is also an unlikely initiator of a new Helsinki Process — not least because, for Russia and its authoritarian neighbors, the OSCE is seen as an instrument of Western policy.

Potential initiators could include the Eastern bloc of EU countries, with meaningful roles possible for the diplomatic services of individual states or configurations — such as Finland, Sweden, Poland, Hungary, Czechia , Romania, Slovakia, and the Baltic States. For the diplomatic corps of these countries, leadership in shaping a new foundation for regional stability could represent a significant achievement.

At present, such a scenario may seem utopian — or at best a distant prospect. But what if it is the only viable one?