This translation was generated using artificial intelligence. We strive for accuracy and quality, but automated translations may contain errors. You can read the original text here.

Discussions about Belarusian foreign policy usually fall into the trap of a geopolitical choice between the West and Russia. Shelter theory allows us to look at the challenge differently — not as a matter of choosing a side, but of diversifying ties to promote autonomy and sovereignty. By Anton Radniankou.

Since coming to power, Aliaksandr Lukashenka has opted for close cooperation with Russia. From his perspective, it was a completely rational and pragmatic choice, but one that conceals the greatest threat to the country’s independence.

The democratic community, by contrast, looks to Europe and chooses EU accession. A valid choice, but in today’s — and even tomorrow’s — conditions, it appears completely unrealistic.

The majority of Belarusians would like to maintain equally good relations with both Russia and the West (and other countries around the world), avoid being drawn into external conflicts, and remain neutral. But right now we live in a polarized world where there is less and less room for neutrality.

As a result: what exists now satisfies no one; what people would like seems unrealistic.

What small countries should do

The relatively new “The Theory of Shelter”, developed by Icelandic researcher Baldur Thorhallsson, explains the behavior of small states in such circumstances well. For survival and development, small countries need more than just to be “innovative, flexible, and resilient”. They remain highly vulnerable to external or internal shocks, dependent on developments in the global economy or politics.

To withstand such shocks, small countries must have political, economic, and social shelters that compensate for lacking resources to defend their territory, political system, national economy, and financial sector.

Such shelters may be provided by international organizations — such as the EU or NATO for the Baltic countries — or by individual countries, like the USA for South Korea. Often, a country can have several shelters to cover different needs.

Without a shelter — a strong external partner — small countries remain alone in the face of global or regional crises. The theory itself was born in Iceland, which in 2008, amid the global financial crisis, saw its financial sector collapse and had no external actors willing to rescue it. Having lost Russia’s support, Armenia suffered military defeat in 2020 by Azerbaijan, which, in turn, chose Turkey as its political shelter.

Russia’s war against Ukraine is an example of the risk tied to shelter switching: the old shelter was lost, and the new one was not prepared for such risks, leaving the country without necessary external defense.

Was Belarusian multi-vector foreign policy real?

Shelter theory helps to re-evaluate the period from 2014 to 2020. During that time, Belarus distanced itself from Russia’s actions in Crimea and Donbas, and those years are considered a heyday of Belarusian multivector policy.

But on closer inspection, it looks more like a deliberately crafted illusion than real substantive change. Russia remained the main political, military, and economic partner throughout, and multivectorism was more an aspiration than reality.

This period showed that even with political will, replacing an economic and military shelter is a far longer and more complex process. Even though Belarus had good political relations with the EU, its export share to Russia decreased only from about 45% to 40%, while EU exports rose from 25% to 30%. In security terms, although Belarus relinquished its military base in 2017, military cooperation did not decrease.

Comparison of Belarus’s “shelters”: before and after 2020

| Type of Shelter | 2014–2020 | Post‑2020 |

| Political | Russia, EU, China | Russia, China |

| Economic | Russia, EU | Russia |

| Social | EU, Russia | Russia |

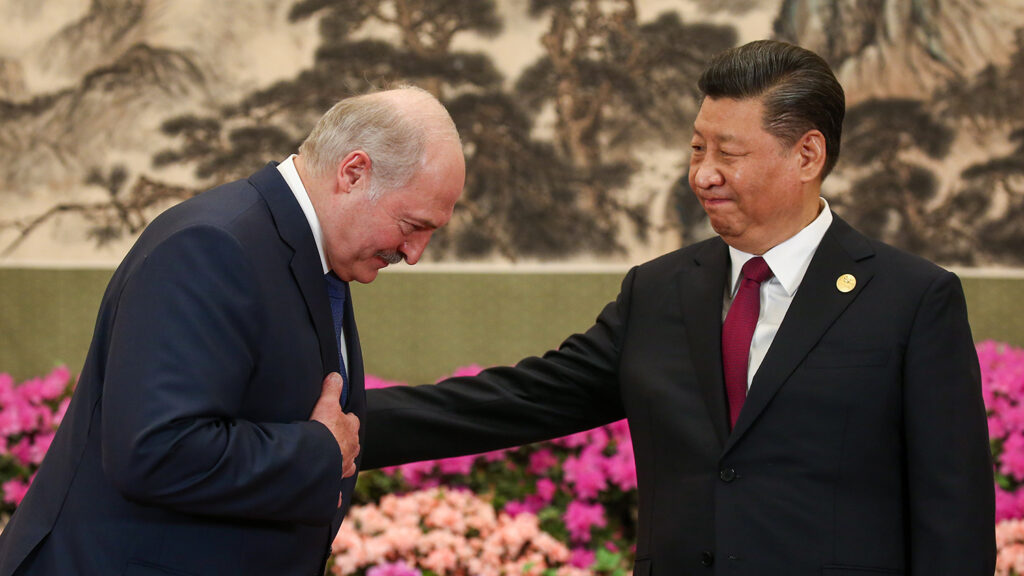

The post-2020 period buried Minsk’s ability to balance between Russia and the West in foreign policy, leaving it almost entirely dependent on Moscow. And although the authorities (and state media) try to position China as a second major partner, investments and credit support from China have not reached pre-2020 levels.

A New World Around Us

Meanwhile, the global order is undergoing transformation. The “collective West” is becoming less collective: there is a clear divide between the United States and the European Union, and democratic countries increasingly act individually based on their national interests.

China, increasingly viewed as an alternative center of global power, faces its own economic and demographic challenges, the solutions to which remain unclear.

None of the major or medium powers want domination by China or the US. On the contrary, all the key players prioritize developing their own strategic autonomy and reducing dependence on other countries.

Three conclusions for Belarus

Shelter theory doesn’t provide all the answers, but it offers ways to expand autonomy and highlights the limitations of small states on this path.

First conclusion: for survival and development, small states are forced to seek a sheltering country or organization. Neutrality, balancing, and hedging strategies can be pursued by medium-sized countries that are less vulnerable to external and internal shocks. This applies especially to security — the weakest point of all small countries. The recent example of Finland shows how, at the first real opportunity, the country abandoned neutrality and balancing, choosing NATO as a military shelter.

In Belarus’s case, Russia has remained its main shelter for nearly the entire period of independence. But what previously looked like “guarantees” has now turned into near-total dependence, creating an existential threat to Belarusian statehood.

Second conclusion: fully replacing Russia as a main shelter with another country or organization looks like an unattainable goal. First, the EU and other Western players are not yet ready to offer Belarus the same level of support capable of competing with Russian influence. Second, a sharp reorientation could provoke a political and economic conflict with Moscow — without a guarantee that a Western shelter would be effective.

Supporters of democratic change must accept that instead of dreaming about a European future, it is more practical to think about reducing dependency and crafting a new cautious policy toward Russia.

It is evident that Belarus must increase the portfolio of sheltering countries and organizations. Belarus’s neighbors in the region are most interested in its sovereignty: they traditionally needed a buffer against Russia — a role that Belarus once fulfilled.

A ‘belt of neighborhood’ must be built — restoring open and pragmatic relations with regional neighbors: Poland, Lithuania, Germany, Sweden. This will improve national security and align with their strategic interests in the region. Such a network of shelters and micro-alliances can be expanded to include other post-Soviet countries also working to reduce dependence on Russia.

Third conclusion: without normalizing relations with neighbors and the EU as a whole, it will be impossible to fix the situation in foreign policy. And no matter how much today’s authorities highlight successes with the “far arc,” China, and African countries — they must understand that dependence on Russia has shifted from ‘beneficial’ to ‘dangerous’.

However, while a political pivot toward a more balanced foreign policy might be carried out within a few years, reducing economic and military dependence may take decades.

Reducing economic isolation could lead not only to the return of the EU as the second main export destination but also to increased Chinese interest in Belarus. Alongside this, international financial institutions would return to the country.

Expanding social shelters is no less important for small countries. It brings an influx of new practices, ideas, and innovations into society, allowing it to grow instead of stagnate. Ties with the Western scientific and educational community will eventually give a boost to the economy. A well-developed diaspora can become a driver of these processes and help grow business contacts.

Ultimately, the new foreign policy must become a gradual strategy to increase autonomy, built on pragmatism and political neutrality. It’s not about choosing between East and West — it’s about expanding our own room for action and maneuver.