This translation was generated using artificial intelligence. We strive for accuracy and quality, but automated translations may contain errors. You can read the original text here.

For many years, Western countries and international organizations spent sums that could have transformed entire industries, cities, and institutions on promoting good governance in Belarus. But why did foreign aid not lead to the expected changes in governance? By Natalia Ryabova.

Against the backdrop of US actions in Venezuela, Washington’s relations with official Minsk, visits, and the release of political prisoners take on new meaning. According to rumors, one of the points discussed was the return of the embassy to Minsk. It can be cautiously assumed that if relations between Lukashenko’s regime and the West gain momentum, then after the lifting of a significant part of the sanctions, releases, and normalization of diplomatic relations, the time will come to resume funding for projects in the country, primarily infrastructure projects. What does the past experience of international actors in Belarus tell us?

Western states and international organizations have traditionally been involved in promoting democracy, part of which is promoting the principles of good governance. According to estimates by the project “Research on Good Governance in the Context of Authoritarian Consolidation: The Case of Belarus (InGAC)”, between 2014 and 2025, various international actors spent around €753 million on promoting good governance in Belarus. This amounted to almost half of the country’s official development assistance (ODA). However, any transformations in governance that may have taken place ended in 2020, and Belarus has cemented its status as a “closed autocracy” — the only one in Eastern Europe, according to V-DEM.

Two approaches, one result: technocracy vs. transformation

The promotion of good governance followed two parallel paths: technocratic and transformational. For a long time, the technocratic approach dominated, with funds allocated to changes that did not affect governance principles. These projects improved administrative resources, infrastructure, and public services, and stabilized the economy without touching on politically sensitive issues.

The transformational approach involved changes not only in terms of new infrastructure (e.g., renovated border crossings), but also in the management of various spheres of public life, as well as the introduction of principles of good governance, transparency, accountability, civic participation, efficiency, and others. Since 2014, the EU has funded 35 projects worth €67.7 million to improve governance. USAID has supported regulatory reforms as part of Doing Business. The United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) has implemented 14 projects worth €19.2 million, often in cooperation with the EU.

However, the bulk of the funds for promoting good governance were still spent on large infrastructure projects. The World Bank invested around €617 million in roads, hospitals, forestry, and utilities between 2014 and 2020 – these projects were accompanied by requirements to reform governance and its principles.

Both approaches to promoting good governance in Belarus faced limitations. For example, the Belarusian authorities rejected a $3 billion agreement with the IMF in 2016 because the requirements for reforming state-owned enterprises, price liberalization, and fiscal transparency threatened, in their opinion, the state economic model. Even during the “golden period” of EU-Belarus cooperation (2014-2020), the parties were unable to agree on projects with a clear normative agenda—for example, a project on large-scale public administration reform was never launched.

An analysis of the volume of assistance in the area of promoting good governance reveals a paradox: even when international assistance for reforms and good governance in 2015 was comparable to 2.16% of Belarus’ consolidated budget, it did not have much political influence and did not lead to significant changes or reforms in public administration.

The Presidential Administration as gatekeeper

There are strict rules with numerous restrictions for any international aid projects in Belarus. The key institution that decides whether to launch an international cooperation project has been and remains the Presidential Administration. It acts as the final authority and determines the “red lines.” These invisible barriers are unwritten informal rules that are nevertheless intuitively understood by people working within the state apparatus or interacting with it. Belarusian officials perceived them as something “political” – something aimed at transforming the system of power itself or potentially calling into question Lukashenko’s authority.

At the same time, as the study shows, the human factor and specific personalities played a decisive role in promoting good governance in Belarus. Reform-minded officials were the driving force behind progress in this regard. In particular, those who worked in financial and economic ministries and departments, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and at the local level. However, they all faced restrictions from other ministries and the most significant obstacle from the Presidential Administration.

Until 2020, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs occupied a special position. On the one hand, it was often the entry point for international projects and promoted cooperation, while on the other hand, it only participated in “safe” projects: accession to the WTO, sustainable development goals (SDGs), cross-border cooperation, and the like. When promoting projects with “dangerous” words (such as “good governance” or civic participation), they were rephrased into neutral terms such as ‘modernization’ or “cooperation.”

The turning point of 2020-2022: collaboration replaced by co-optation

After the political crisis of 2020 and the start of the war in 2022, most international organizations and governments of democratic countries suspended cooperation with the Belarusian state structures. However, some of them remained in the country. The composition of actors changed: instead of the World Bank and the EU, the leading players became the UNDP and the International Organization for Migration (IOM). A new actor supporting international projects in the field of governance was the UN Multi-Partner Trust Fund for SDGs, supported by Russia.

The activities of the “survivors” have become more technical and narrow in scope, resembling co-optation rather than cooperation. Thus, in 2021-2025, only nine new projects with a total value of €3.5 million were launched, focusing primarily on technical, administrative, and infrastructural elements of governance, but not on the implementation of good governance as such. The topics of the projects from 2021 include:

- Migration management (4 projects worth €894,000 with the Ministry of Internal Affairs, Ministry of Health, and State Customs Committee)

- Nuclear safety (€375,000 with the Ministry of Health)

- Biodiversity and climate (€296,000 with the Ministry of Natural Resources)

The transparency and accessibility of information about the projects themselves have also decreased: their partners, activities, and results are often not published in the public domain.

Lessons for international actors

So, as the study shows, although the funds of international actors were generally spent wisely and for good causes, they did not lead to sustainable changes in the governance system itself, as evidenced by the rollback after 2020. What conclusions and lessons can be drawn from this experience?

1. Volume does not equal influence. As the Belarusian authorities wanted, most projects and funds for promoting good governance were and are directed towards infrastructure and other technocratic and administrative changes, rather than towards transformations affecting the values and principles of governance. This did not change the system of public administration and did not create effective levers of pressure on it.

2. The “red lines” are invisible, but they are not crossed. Even reform-minded officials in the ministries could not overcome the veto of the Presidential Administration and other conservatives within the Belarusian system, who blocked any initiatives affecting the political sphere. International organizations that refused to adapt and accept such rules of the game simply had their projects rejected.

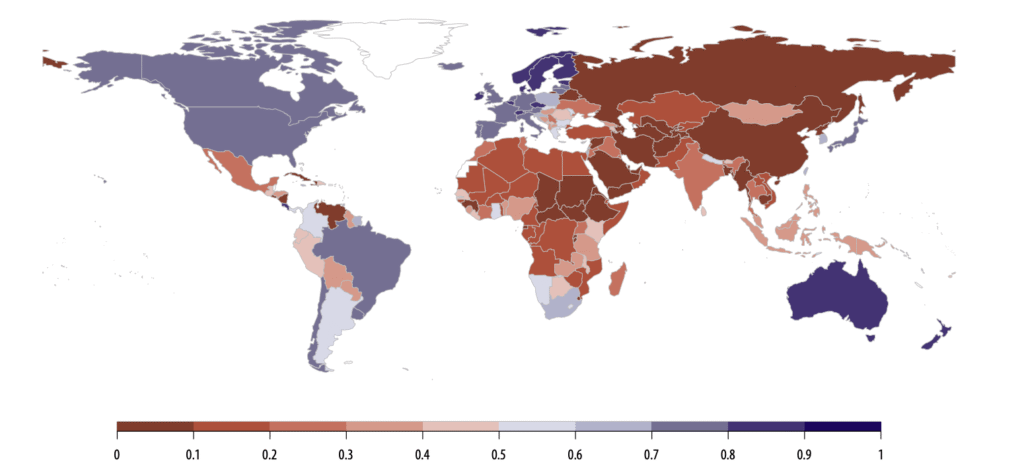

3. Technocratic assistance in an authoritarian context can backfire. Improvements in international indices, such as Doing Business (rising from 45th place in 2015 to 37th in 2020) and the E-Government Development Index (EGDI), were used for legitimization but did not lead to openness. The government unabashedly attributed improvements in public services and infrastructure, financed by donors, to its own efforts. In a number of cases, digitalization is used as a tool to persecute and pressure political opponents and citizens, rather than as a means to ensure transparency in public administration.

4. After 2020, co-optation replaced cooperation in the promotion of good governance. International organizations that have remained in Belarus are forced to adapt to the new conditions. Their efforts may lead to some minor improvements in governance, but strategically, they tend to help the authoritarian government obtain additional resources and improve its administrative capabilities.

What is the outcome?

In October 2025, the International Monetary Fund resumed dialogue with Belarus in an online format after a three-year hiatus. In the same year, the International Organization for Migration launched a new project to strengthen the capacity of the State Border Committee in response to increased migration. If international actors expand their engagement with Belarus and, at some point, for whatever reason, decide to resume active cooperation with the Belarusian government and support projects within the country, it is important to ensure that there is real political will and leverage.

Otherwise, external investment in reforms may turn from a means of promoting good governance into a tool and source of funding for the consolidation of the regime.